Passionate Abolitionist and

Witness to the American Civil War

Passionate Abolitionist and

Witness to the American Civil War

In 1829, Thomas Jackson arrived in the United States in his early twenties, equipped with ropemaking skills and all that a childhood in Ilkeston had provided. Not least he possessed a passion for liberty and justice for those who were wrongly and grossly mistreated, expressed in his own formidable and fluent writing style. His letters and articles, written throughout his nearly sixty years in Reading, Pennsylvania, beg the question: how did a working ropemaker, born in a modest, English Midlands town at the start of the 19th century, gain these values, opinions and abilities?

We can offer one good answer: his father John had a lot to do with it.

Faith Thomas’ father John Jackson was born in Ilkeston in 1764 to Presbyterian parents Charles Jackson, who was a chandler, and Elizabeth Coates, from nearby Selston in Nottinghamshire. Both parents were likely descendants of dissenting ministers of the 17th century – Rev Charles Jackson and Rev Samuel Coates, both with Selston connections. John’s family was comfortably off and well-respected by the strong, non-conformist community in Ilkeston. In Thomas’ early life, in the 1780s and 1790s, Britain was abuzz with reformist and radical ideas and activism, much of it powered by dissenting faith, of the evangelical kind. Thomas Jackson’s writings exemplify that same powerful, no-holds-barred, moral and evangelical belief and style.

“The Eighteenth Century English Dissenters’ involvement in and contribution to the cause of liberty is well-established. Possessed of an insecure toleration, still victimized by [laws] and subjected to sporadic persecution, the Dissenters fought a century-long campaign for religious and civil liberties.”

Education We can see clearly that Thomas must have had a good education, even at a time when no ‘State Schools’ existed in England, although the Sunday School Movement of the time may have provided the basics of literacy and numeracy. In some letters he talks nostalgically of ‘John Mason’s school’ which we know little about – but the Masons were among the leading non-conformists in Ilkeston. A family committed to the Independent faith almost certainly had education passed down for generations, by families and ministers, and conveyed it further to John and his three sisters and then to Thomas and his six sibs. As dissenters, Thomas’s mother Ann and grandmother Elizabeth were possible educators too.

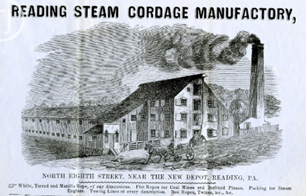

Occupation and enterprise From a range of records, we learn that John Jackson had the skills and confidence to operate a ropery on a lease from local entrepreneurs Hollins and Oldknow, converting an unsaleable, modern cotton mill by the Erewash Canal at his own expense into a covered ropewalk. He took on a mortgage in 1806, when Thomas was a babe in arms, to purchase these premises. And he proudly announced in 1813 a machine he had created for manufacturing ‘Flat Ropes’, the latest development vital to new industrial processes using winding mechanisms. Surely John’s sons gained their ropemaking apprenticeships and skills with their father, as well as an enterprising frame of mind – Thomas advertised flat ropes amongst his own products in America.

covered ropewalk. He took on a mortgage in 1806, when Thomas was a babe in arms, to purchase these premises. And he proudly announced in 1813 a machine he had created for manufacturing ‘Flat Ropes’, the latest development vital to new industrial processes using winding mechanisms. Surely John’s sons gained their ropemaking apprenticeships and skills with their father, as well as an enterprising frame of mind – Thomas advertised flat ropes amongst his own products in America.

Hard times Enterprise can go well, as it seems to have done for John for a decade and more, but it can also go wrong. In 1815, John was declared bankrupt and was forced to sell his business to avoid ruin.

Wealthier Ilkeston non-conformist James Potter purchased the ropery and then, reportedly, continued to employ John (and no doubt his sons) to operate it. Even though only a child, aged about 10 or 11, Thomas must still have been affected by the change in circumstances, and even more so a decade later in 1825-6 when his half-brother, John Jackson junior, also faced bankruptcy – and was also seemingly rescued at the last moment by well-wishers. But this may have been the point when Thomas and brother Edward – perhaps others of their family too – were forced to work elsewhere as ‘jobbing’ ropeworkers. This may be why Thomas arrived in Handsworth by Birmingham and probably, in his own words, was the ‘misfortune’ that drove him to emigrate. More importantly, these early experiences could explain why he exhibited such great strength in adversity during his life in Reading. Three times his works were destroyed by floods and even by arson but he rebuilt them and his prospects with determination.

A stand for what is right In 1794, John Jackson was convicted of the crimes of sedition and blasphemy, sentenced to an hour in Derby Market Square’s pillory and a year’s imprisonment in Derby County Gaol. This happened ten years before marriage and children, but in Thomas’ articles for local PA newspapers, he describes how John told him this story, and the price paid for his principles:

“We and our whole family, have ever been in favor of free principles and

republican government, and our father, who is now no more, suffered a long

imprisonment, much hardship and persecution from the government of

George the III of England, entirely for his love of liberty.”

Both pillory and imprisonment in the 1790s were horrendous affairs and John Jackson was the most harshly treated person convicted of sedition in Derbyshire during the period that Government and George III clamped down on radicalism. His crime had simply been to distribute copies of a protest leaflet he had neither written nor printed himself. Along with that, which must have been a shocking story for a small boy to hear, John also imbued in Thomas his admiration for the new republican form of Government in America, its principles of liberty and freedom for all. To sum him up: John was an educated man, reading the radical news and publications of the day and sharing it with Thomas in his growing-up years.

A word about slavery As an educated, reading man of the period, John Jackson could not have escaped the information regularly shared by the local, radical press about slavery’s horrors and the significant abolitionist movement in Britain. Dissenters were especially moved by anti-slavery principles and these ideas were surely part of the air that the Jackson family breathed.

Thomas insisted in his article describing his revolted and appalled feelings at the first sight of a slave market in Richmond that his father never mentioned ‘American slavery’. Possibly true, since Britain’s focus was mostly on Caribbean slavery. But this wording was perhaps more likely a way to express the degree of personal horror when seeing the truth in a country supposedly founded on freedom for all. It is close to certain Thomas had acquired anti-slavery views from father, faith community and the press in England – and these principles powered his life, actions and letters to the date of his death in 1878.

Full details of John Jackson’s life and family can be found here: [link to Final Draft article]

____________________________________________________________________

Celia Renshaw BA MA is a family historian and writer specialising in Derbyshire, the East Midlands, 17th and 18th century Dissent, emigration to the US and historical connections of British families to slavery.

Contact: celiarenshaw@gmail.com. Web: www.morgansite.wordpress.com.

[1] ‘The Origins of British Radicalism: The Changing Rationale for Dissent’ by Russell E Richey, in: Eighteenth Century Studies, Vol.7, No.2 (Winter 1973-4), pp179-192.

[2] Thomas Jackson letter to the Berks & Schuylkill Journal, 26 October 1844.