Passionate Abolitionist and

Witness to the American Civil War

Passionate Abolitionist and

Witness to the American Civil War

The People Who unearthed the TJ Story

Thomas Jackson sought the help of his English cousins Caleb & William Slater to get his words heard across the miles during the civil war.

Now in order to get his words also heard across the years, Thomas would want us to thank the extensive community of remarkably diverse people who contributed their expertise and encouragement to allow his spirit and his fierce commitment to abolish slavery and to promote freedom to be heard again.

Here are just some of those who have been most helpful.

Irvin Rathman and his fellow volunteers – Historical Society of Berks County.

Irvin took a chaotic collection of photocopies of many of these letters and meticulously transcribed and organized them and thus gave life to this whole project. He has continued to add astonishing depth to our understanding of the Thomas Jackson story ever since. So much so that if there is one person whose support, historical knowledge and dedication has brought the TJ letters into the light of the 21st century, it would be Irvin. For over two decades, he has shown a unremitting dedication to make the TJ story as complete as possible;

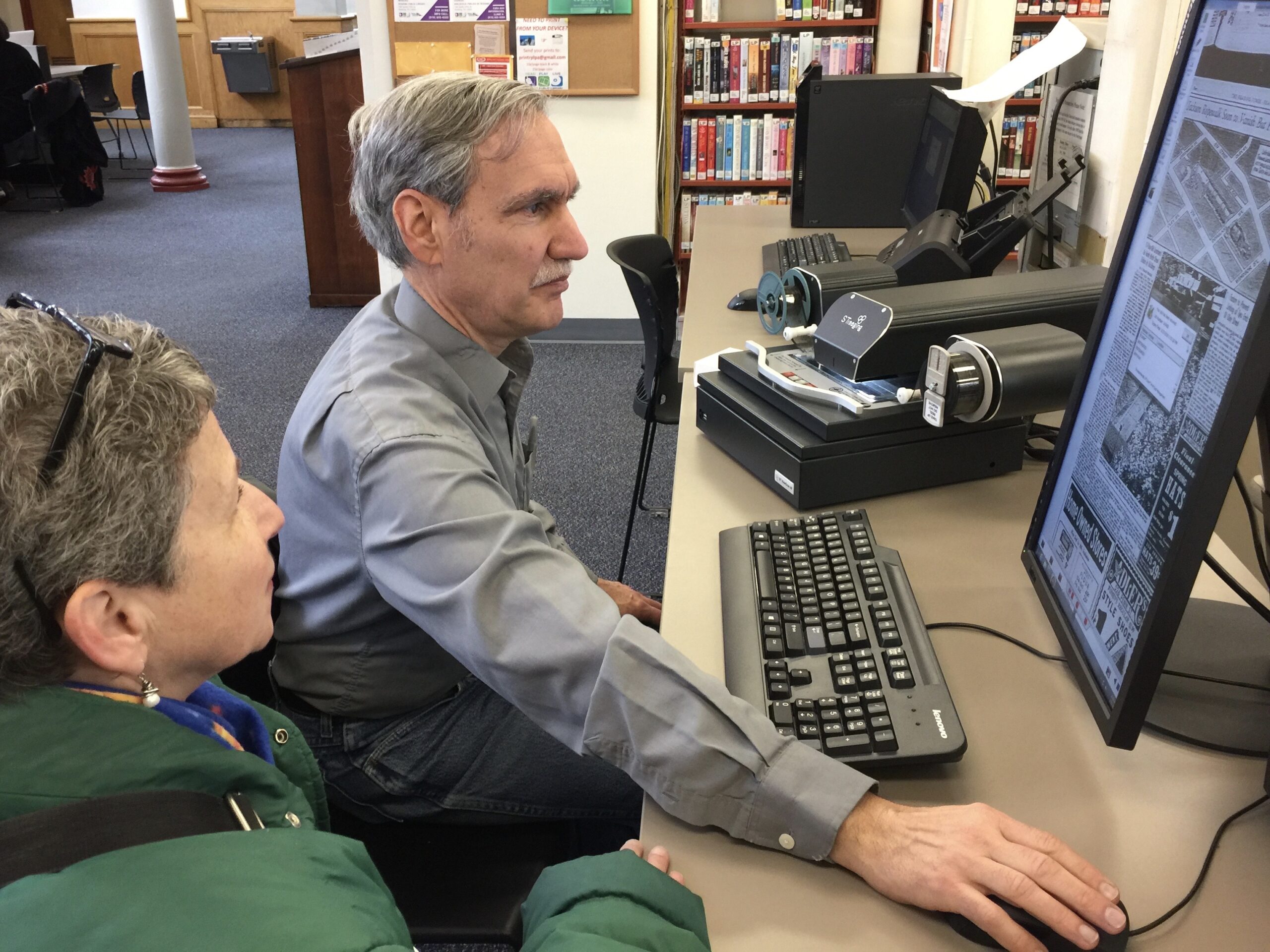

Irvin Rathman with colleague Lisa Adams

Neil Scheidt also from Reading who has provided extensive assistance in discovering the genealogy of Thomas Jackson and Caleb Slater and their relatives as well as unearthing important details of T J’s life in Reading. Neil is a prolific contributor to documenting the memorials and dedications of individuals from past generations, particularly US veterans.

He alone has documented over 67,867 (yes! ) memorial records in Findagrave. He too has been a patient and ever supportive resource of the Thomas Jackson project from our earliest days.

Neil Scheidt with first digital record of TJ’s grave

Phil Whiddon, Livewire Web Design, was our first web designer who literally drafted out the format for our original website on the back of an envelope as the depths of our project were first described to him. The appeal of our project for the first decade of our existence was fueled by his enthusiastic commitment to take the scans and transcriptions of the many old manuscripts and present them in a digital format while keeping the feel of the vintage period from which they arose.

He left the project with a format that is easily navigated and expandable so that it appropriately displays TJ’s historical observations through the medium of modern technologies.

Phil Whiddon whose early design for the site added to its universal appeal.

Frank Ward, another early member of our team whose encouragement and endless enthusiasm for the project has continued until the present day. It was he who transformed the Ambassadors’’ minds when he recognized from the piles of the then disorganized letters that TJ’s ongoing driving force was working to abolish slavery. (Easy to see now but not so as we were ploughing through piles of letters by many authors covering an enormous variety of topics.)

Michelle Krowl, Civil War and Reconstruction Specialist, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress who has been a major blessing to our project in that her interest and encouragement reinforced our on-going efforts that this huge project was indeed worth continuing. She helped keep our light of passion alight when we came to recognize that our intended “just a few months” turned into nearly two decades of time devoted to different aspects of the project. Her constant willingness to give professional input and fresh perspectives have ben a constant source of positive energy to our project.

Michael Knight (US National Archives & Records Administration) was the first person with a nationally recognized reputation to read the materials in detail and offer his detailed personal assessment of the high historical value of the collection. Until then, the Ambassadors had no confidence that all those old and disorganized documents were of major value as a unique window to the civil war.

In addition, here are just some of the many others, most who would never think of themselves as historians, who gave significant support:

Jan Swanbeck (Documents Librarian, University of Florida)

Joe Aufmuth & Carol McAuliffe (Also librarians, University of Florida)

Stephanie Birch (Librarian in African American Studies at Unversities of Florida and Connecticut. (For analyzing all the site’s contents and producing the basis of our topic search feature)

Lisa Adams, Kimberly R. Brown and their colleagues of Historical Society of Berks County, Reading PA.

George M. Meiser & Gloria Jean Meiser. Authors “The Passing Scene” series of books on the history of Reading and Berks, PA

Bill Rehr (Former fire chief for Reading for records about the arson attacks on TJ’s business.)

Ron Devlin (Historian & Reporter for Reading Eagle)

Leila and Don Lohr (Friends who’s own enthusiasms for the raw materials were the basis of our Highlights section)

Maria Miller. (Transcriber & versatile assistant during the Covid Pandemic)

Alyssa Lewis (Transcriber & dedicated assistant during the Covid Pandemic)

Jamison Davis (Virginia Historical Society)

Stephen Spears (Author for advice)

Deborah Hendrix (A multitalented video and digital technologist from Department of Oral History at UF)

John Sensbach (History Faculty, University of Florida)

Jerry Sanford (Collaborator)

John Huddleston (Collaborator)

Parker & Natalie Small (long term friends and wise humanitarians)

Barbara Oberlander & Donna Waller (Respected civil war historians)

Marilyn Mundy (US National Archives & Records Administration)

Alexia Fernandez (for help in transcribing letters and professional journalist.)

Sally &Andrew Casey (English relatives of the David Machin, the second Ambassador)

Gina & Peter Donaldson (English relatives of the David Machin, the second Ambassador)

Tricia & James Falconer Smith (long term English friends, with their own family history collections)

Dianne Irish (ever patient and supportive wife and life partner. No words of gratitude could ever be adequate.)

Robert Elliott (long enduring and generous supporter)

James Lazarus (constant enthusiast and invariable optimist for life)

WEB DESIGNERS

Dennis Plunkett and staff at Jumpem (for transferring the old HTML site to WordPress format)

Ashley Thibodeau and Tara Jones at Digital Design Solutions for finishing the conversion of the old WordPress site into two sections, one optimized for mobile media (thomasjacksonletters.org) and one for computers (thomasjacksonletters.com)

Rich & Chris at Anologix for completing the many unfinished digital components of this voluminous project.

A review by John Paling after working on the project for ten years. It explains in some detail how Thomas Jackson, an unknown nineteenth century rope-maker from Reading,PA, emerged as being an inspiring new citizen of America who dedicated his life to trying to abolish slavery.

It feels appropriate to explain first why I have spent so long recording some of the main steps that went into unearthing such a detailed record of Thomas Jackson’s life story while building an on-going series of attractive websites to share his writings with others.

Initially writing this account of the background to our project was not my idea. Instead, it was started following an unexpected request from our friends at the Library of Congress. (Only a Librarian would think along the following lines!)

In essence, they pointed out that it was often difficult to predict in advance what researchers would dig out from the various original documents that the LoC curates but there was one thing that they could be sure of. It was this. In years-to-come historians of communications would be looking back for clear evidence about how ordinary folk of the time struggled to embrace the new technologies.

For example, you can understand how historians would be interested in learning how people following 1440 were impacted by Gutenberg’s movable type printing press. How did that invention effect society of the time? Similarly, in the distant future, some historians will be seeking source materials to understand what were the impacts of today’s digital technologies for ordinary people and the ability to research and publish. Once you become aware of this concept, you can see that our struggles with ever-changing digital technologies over ten – now 22 – years might make a useful collection of documents to add to many others specifically saved by LoC with the objective of making them available to social historians in the years ahead.

Once you are aware that we have been asked to support a LoC “project within a project” you will appreciate why I record the people and our challenges when I write about the background of the TJ Project.

In addition, we have been asked to bequeath all our emails and other digital communications to LoC in case some (?misguided) historian in 200 years time feels that our challenges of trying (and often failing) to use digital technologies may serve as part of some useful insight for others in far off times.

And we have certainly had challenges. I don’t think the LoC could have been aware of it but I (born nearly 50 years before computers became commonly available) seem to spend half my days battling the digital world.

As a result I have joked that LoC will come to hold the papers from three diverse characters from this generation.It will have Steve Jobs who founded Apple; Bill Gates and his associates who gave us Android; and now, to provide some counter balance, it will have JP who finds digital technology a pain in the butt and hence qualifies for the name Hemorrhoid Paling. And that is how future historians will find I sign my name in emails to LoC.

**************

The Thomas Jackson letters are part of a collection of original family letters that came into the consciousness of John Paling during the second world war in England. The letters were from many different people and were jumbled together in a battered old brown metal hat box that was stored in the back of the cupboard under the stairs of the family’s little duplet. On occasions in the past, John’s mother had tried to make sense of them as she had discovered that many of them were very old and had apparently been written by some unknown Americans our little family knew nothing about. Whenever she tried to sort them out, she inevitably found that, after two or three hours trying to sample them, they remained largely untouched and overwhelmingly confusing.

As a result, they were simply bundled up and put back in the hat box for someone else to deal with.

During the war time, John recalls that the contents of the hat box were rarely examined. When they were, he remembers being impressed by the beautifully neat handwriting on some of the letters but he resented his mother’s repeated suggestion that when he grew up, he should be able to write as well as those old folk did.

More interesting to a young boy’s mind were the old stamps on the letters. He now recognizes that many of them represented some of the earliest postage stamps ever issued but with few games or toys available during war-time England, he and his mother carefully removed every stamp from every envelope in the collection and presumably stuck them in some now-lost album!

Other letters were back from the pre-postage stamp era and were simply folded over and kept together with sealing wax. The possibility that any of these letters and envelopes might have any historical importance never crossed the minds of a war-focused family. It was only 60 years later after he retired and had become an American citizen that John was drawn to taking another look at what is now known as the Thomas Jackson collection.

HOW THE DISCOVERIES PROGRESSED

(An old man’s personal anecdotage prompted by a request from the Library of Congress)

When I poked into the letters again, I immediately became captivated by the eloquent and passionate writing of someone who signed himself Thomas Jackson. However along with these letters there were many from other people, most written on flimsy paper that were near impossible to read and thus difficult to see why they had been bundled up in the same collection. Because of the price of international postage in those early days of distant communication, many sheets were not only written on both sides but were inscribed in two directions on each side as well. And to add to the general muddle there were unmatched envelopes, loose sheets from incomplete letters, odd bills and property records and engraved pictures of factories for rope making.

What was immediately clear was that while these letters might offer an interesting window into someone’s long lost family, there was no way that I was going to spend my time trying to sort out and analyze that disorganized mess of handwritten sheets. I was not a historian. Hated all the boring detailed learning at school. (Only got 18% in the annual exam much to my mother’s grave concern. Almost matched her worry at seeing a much earlier note from a primary school teacher that did not bode well for my future: “The dawn of legibility in his handwriting reveals an utter incapacity to spell!”)

But this heap of letters clearly fell into a category of past family “stuff” that every adult who has cleared up another’s estate will recognize. I certainly didn’t want to hang on to them but they were too important to just throw in the garbage. And it did not feel right to pass them on to the next generation once again. That, after all, was how I finished up with the unwanted task of dealing with them in the first place. I also knew instinctively that my mother would expect me to “do the right thing with them”, not as a burden but rather out of simple respect for the family’s sense of responsibility.

It is relevant for understanding the Thomas Jackson story to know that I had the huge good fortune to be brought up as an only child of deeply loving parents. We were very much a working class family. My father worked as a mechanic in a clothing factory and, while we never owned a car or a telephone, I was enveloped by unlimited love and support all through my life. My mother’s maiden name was Slater and her closest friend was her sister who lived with her husband and sons about 30 miles away where the family had deep roots. We would visit each other several times a year (taking the best part of a day walking to the station, then taking a train and finally a bus to get there). The sons and I became close as we grew up together, especially the oldest David.

Given my attitude, my strategy for the letters was obvious. Quickly sort through just the easy-to-read Thomas Jackson letters, make some sample photocopies and offer them to other folk who might have some use for them and thus take them off my hands. That became a trap that took over ten years of my life!

When I assembled a few of them in sequence and tried to learn how the author might be related to my life, many interesting things emerged. The pages were packed full of information that at first was difficult to get my head around.

First Thomas Jackson was writing from Reading, Pennsylvania to Caleb Slater my great, great grandfather in England. He addressed him as “Cousin” and spoke of how they grew up together in rope making families in rural England. All the letters that remained were from America giving no indication of how or why Thomas had moved to America in the first place or indeed anything about his family while in England.

But what was evident was that many of the later letters were bursting with passionate reports of the ongoing American civil war and the horrific injustices of slavery. There was even a heart wrenching article about witnessing a slave market written by Thomas Jackson and published in a local English newspaper.

Clearly this man was recording his first hand experiences of momentous events in the history of his young country as they were unfolding. All interesting material but not for me. (Candidly, part of the appeal of the letters for me was still the aesthetics – the artistic handwriting and his rich use of the English language.) But the letters raised almost as many questions as they answered. How could he write one letter with 18 long pages of detailed text in the gloom of candlelight and have virtually no corrections? Had there been earlier drafts? How did he know about the intricate details of the civil war both local and national? Where had he got his education from to be able to communicate his experiences so powerfully?

I rationalized that the more I could find out about this shadowy relative, the better I could make a case for some organization to accept the Thomas Jackson letters and do justice to promote the depth of detailed historical information that they contained. Time to use digital searches.

(As background, everyone should know that I truly believe that I radiate a negative energy that causes electronic equipments and software programs to fail, fumble and frustrate in all basic operations. My negative powers effect not just my own equipments but also those of other people in the same room. Experienced computer consultants will confirm that i really do seem to possess inexplicable powers that (honestly) render half of most days on computers devoted to dealing with failed operations.

I once was involved in advising the American military about the existence of a small fly that can stop bullets from a gun in mid air (true- might have helped aerial intercept technology) but these days I think I should return to offer my services to bring down enemy drones by virtue of my propensities to deliver digital devastation.) So with no great optimism, I set out to see what the web might teach me about Thomas Jackson.

To my amazement, the web had pages and pages and pages on Thomas Jackson. But to my surprise, it was all devoted, not to my newly discovered relative but to some southern general “Stonewall Jackson”- about whom, being deficient in history, i knew little and certainly didn’t know he was also a Thomas. In summary, despite repeated searches in different places, I could find nothing. What was I expecting? “My” Thomas Jackson was obviously of no importance and there was no reason to think that he would feature on the web any way. So that just reinforced my wish to get rid of these somewhat burdensome family letters by quickly finding some organization to pass them on to.

Searching on the web again, I did find that Thomas Jackson’s old home town of Reading, Pennsylvania did have a Historical Society of Berks County centered there and so I sent them a selection of photocopies of some of the longest Jackson’s letters suggesting that they might want to know about more about their illustrious son.

Over time, I came to have useful collaboration with different members of their staff but my memory of early exchanges was that while they seemed eager to take the originals for their collection, they could give me no assurances about how the material would be used if I did donate it. I had anticipated that the proper home for these letters would have researchers or students so that the letters would be used as the basis of some publications to spread the word about Thomas Jackson and his experiences of the civil war from the center of their own city.

I even got that sort of response from other historical institutions that specialized in the civil war too. They saw that the letters might be valuable for historians and rather than turn them down, they just wanted to take possession of them without knowing how they would ever be used. It just confirmed my awareness that if these folks who knew about the value of original civil war documents did not attach any value to what I was offering, then I should just forget it and move on.

A final discouraging commentary on the value of the Thomas Jackson letters came from an officer in a major national library. On being sent copies of most of the letters, he volunteered that his institution would consider taking them but that at that particular time he had funding to buy historical material that might be offered for sale on E-bay or elsewhere on the web. That was his focus. In other words, he would give the Thomas Jackson Letters more attention if they were up for sale rather than if they were being offered for free. Oh the psychological lessons that accompany attempts to give away something of value!

The upshot was that, with no one to give the letters to, I just carried on reading more of the letters as time permitted and tried to piece together all the names and relationships that were mentioned in the text. I started to realize that most others would never be willing to give the time to read these letters in the original handwriting, however neat and elegant the script. My thought was that if I wanted others to access the range of Thomas Jackson’s I should make their job easier by providing a transcription in printed form of some of the letters that seemed most interesting to my eyes. In the absence of having anyone to do that work for me, I devised a method of using the dictation application of my cell phone, something that could not have been done at the start of the project. I took a letter page by page and read it in my clear English accent into a blank email on the phone and then forwarded that to myself on my desk top computer. Then by comparing my attempt at a digital transcription side by side with the original page, I made corrections and finished up with a reasonable version of a few of the letters. But it was a slow and laborious process. Then out of the blue, I received a package that changed the trajectory of the project for ever.

In the mail I received a thick legal envelope packed with meticulously transcribed versions of all of the Thomas Jackson letters that I had sent to the Historical Society of Berks County months before! They came from Irvin Rathman, a volunteer at the organization who had adopted the project and, without me knowing anything about it, had painstakingly transposed the handwriting of the rather slapdash photocopies into modern printed text. (In the light of later experience, I would rate Irv was the most detail-focused historian that I have ever encountered. Others might describe him – admiringly I hope – as “anal”. But for this project, he was- and continues to be- a game changer.

His pages read like a book. They showed me Thomas Jackson in a new light. For the first time, I could appreciate the overall importance of those letters. It now became abundantly clear to me why Thomas Jackson wrote such powerful reports to his cousins back in England and why many of them had virtually no family references or social pleasantries.

At root TJ was appalled by the institution of slavery and wanted to play a part in seeing it abolished. His ingenious strategy was to send first hand reports about slavery and the civil war in America to his relatives in England and get them to get printed in the local newspapers so that voters would not easily allow their British politicians to support the confederate south and thus perpetuate slavery. Thomas Jackson was in fact a firebrand abolitionist who set out to change America by working in a uniquely unconventional way.

Then a relative kindly introduced copies of the letters to Mr Michael Knight of the US National Archives Administration. His personal analytical appraisal removed any remaining doubts about the unique value of the letters on the national stage.

“I am intrigued by the author of the letters. He is a fire breathing unionist who did not serve yet he was extremely well acquainted with military detail and military ordnance (his detailed description of the various artillery pieces caught my eye). He also seems to have more than a passing knowledge of Pennsylvania civics and budgetary issues/procedures, suggesting he served in some civic capacity at some point.

His detailed reporting of the capture and return to bondage of numerous African Americans in Pennsylvania is significant. This has become an area of intense interest in recent years, yet the number of primary sources on this aspect of the campaign have been limited. For that alone the letters are unique.

Additionally, the study of Lincoln has undergone a renaissance in recent years and his description of the reaction to the news of the president’s death is both poignant and historically important. In reporting the death of Lincoln as well as the early information on Lee’s movements during the Gettysburg campaign his information is remarkably accurate-for a man living during these events.

Many other letters of that period have rumors and disinformation with only a few details that stand the test of time.”

Never again would I feel hesitant about proclaiming Thomas Jackson’s historical importance and insisting that the powerful emotions and detailed reporting merited serious respect and an appropriate home for posterity. Furthermore, I then felt that having this confirmation about the importance of the letters would make it easier for me to find someone to study all the collection in detail and use it as the basis of original historical publications, something I still had no intention of taking on.

But little by little, I was picking up more and more details about Thomas Jackson and his relatives while also learning a lot about the American Civil war that was previously unknown to me. But it was becoming increasingly difficult to keep everything that I was learning in perspective. What was needed I thought was a website into which I could funnel and organize my findings. I already had three other professional web sites but this project seemed to be a very different creature.

Enter web designer Phil Whiddon who visited me to discuss the project and while we were together, sketched on the back of an envelope a concept for organizing the material that we came to adopt and has served us well for over the ten years that we have worked on this project together.

I knew that the essence of the site should be high resolution scans of each of the original letters, side by side with a transcription of each page. Because of the amount of material in the collection, we also saw the need for a simple explanatory paragraph and some method of rating the relative importance of each letter so that visitors to the site (if any!) might efficiently focus on what might interest them most. Later we added other family letters and many more digital records to the site and Phil’s original design showed that it could be readily adapted to do everything we wished of it.

My intention had always been to make the Thomas Jackson site appealing to members of the public and not just to academic researchers. For that reason, I insisted we included good relevant visuals throughout the site to make it appealing to the general visitor. A few photos came from illustrations we received from the Reading Historical society, some from paintings and other civil war records we found on the web, some from scans of key parts of an individual Thomas Jackson letter but most were from the photographic archives of the Library of Congress.

All this time, the project was still a part time endeavor. The whole collection was still not organized and while we started to dip into some of letters from other authors, I stored some of the Thomas Jackson letters separately to keep them “safe”. Much later, when we got around to putting these on our website, I found that I had forgotten where “safe” was and for weeks could not recover some of the most important letters in order to rescan them at a high resolution as was needed for historical records. In fact for a time the site had pathetic apologies to tell the readers (?both of them!) that we knew there were these important letters somewhere but they were temporarily lost! In truth we were wallowing in too many loose ends.

We also struggled to make the site seem coherent rather than a series of many separate letters. We agreed that we needed some appropriate background illustration for the home page that was totally in keeping with everything that the whole site was intended to do. As a professional movie photographer for many years in a previous life, I confidently took on that task and covered a table top with artistically arranged copies of the most visually attractive material to make an appealing collage giving the “feel” of the whole collection. The result was OK but really didn’t wow the viewer. But we left it up as another loose end.

Then one evening several weeks later, I was seeking some current family photos from an old chest in my home and unearthed a shirt box that contained all the missing letters! In jubilation, I tossed in on to the dining room table, pulled out a few letters, snapped a photo with my cell phone and sent it to Phil with the news. “Look, I’ve got the missing letters.” The reply came back, “And you’ve also got the master background photo for the whole website!” In retrospect, I could never have captured a better image to convey the character and content of the site.

I was still sending samples of the letters round to different civil war institutions and university research groups in the hope that someone would commit not only to house the Thomas Jackson collection for posterity but also commit to organize, research and publish accounts that did justice to the value of the materials. The latter was always the stumbling block.

Because the author was totally unknown and the collection of letters came with no reputation as to their value and that to view most of the collection required the time to navigate our somewhat scattered website, none one seemed motivated to commit to the project. Every one it seemed had their plates full anyway. Our letters did not appear to have what was needed to break through the threshold of academics’ inertia and result in any of them being eager to incorporate our letters into their research programs.

Another turning point. I received a charming email from Dr Peter Carmichael of Gettysburg Museum who, after being complimentary about Thomas Jackson and his reporting on slavery and the civil war, said “Look, you know this material better than anyone else will do. YOU should take it on yourself!”

An irony: I had been giving more and more time to better understand the collection so that I could give it away. However I had unintentionally made myself the expert on Thomas Jackson’s letters and thus the best qualified to do what I had been trying to get others to do!

So without making a conscious decision to do so, I somehow took on that role and dedicated myself to get everything I knew displayed on the website. By chance I stumbled across some wonderful old maps on the web that showed Thomas Jackson’s rope factories, a canal lock, a general store and a hotel all named after him. But while I was discovering more and more about the writer of these letters as a resident of Reading PA but there was nothing that I could find about his first 22 years growing up in England or his relationship to “cousin Caleb Slater” to whom he addressed many of the letters along with the plea that he “Get them published in the newspapers”.

I realized that the best possibility that I might learn more about the English side of the relationship was to contact my cousin David Machin who was the one remaining son of my mother’s sister, with whom I had grown up and had been my closest friend since childhood. This turned out to be an exquisitely providential collaboration partly because of the number of fortuitous parallels that our relationship shared with that of Thomas Jackson and Caleb Slater.

First, like Thomas Jackson, I had left England and become an American citizen many years before and I was now contacting my own first cousin back in England seeking help from him to add an important dimension to my project. Secondly, like Caleb Slater, David had lived in England all his life not 10 miles from the town where Thomas Jackson was born and grew up. Thirdly, like the two nineteenth century cousins, there was about a decade difference in our ages (the American cousin being the younger in both cases) and we both were both fired with the same firm value of simply wanting to do what was right by our family. All that separated the collaboration of the two sets of transatlantic cousins was about 150 years, two world wars and totally new opportunities for individuals to communicate.

Thus it was that we started to work together hoping to fill in many more of details behind the relationship of Thomas Jackson and his family and Caleb Slater and his. We felt that we were Ambassadors for Thomas Jackson and his letters and so we named ourselves as such.

To this day, we were never able to correct some major imbalances in our knowledge of our two nineteenth century cousins. We have many letters from America sent to the English side of the family but we have located none at all that were sent from England in reply (although we know that many were received in Reading.) In contrast, we have many excellent family photos from our mothers showing the Slater side of the family but not a single likeness of Thomas Jackson from any age of his life. Despite our efforts and the modern resources of digital searches, we remain frustrated by the many remaining gaps in our knowledge of “the Thomas Jackson Story”. (I still wistfully lament that if only I had been successful and found a full time academic research group to take over the project, then I might dump these on-going challenges on them!)

But help from another unexpected source was round the corner. A young woman who had expressed an interest in doing the website for me called to say that her assistant had found a reference to “my” Thomas Jackson on the web but she could not relocate the reference to share it with me.

That was enough to set me off searching the web again and this time, as new materials are being added all the time, I found Thomas Jackson’s gravestone and was able to read the inscriptions upon it. This thrilling and glorious breakthrough had come about from the work of Neil Scheidt, a Reading resident who voluntarily as a public service, goes round grave yards taking photos of the memorials to post them on the web so the people they represented would not be lost to future generations. I discovered that there was a extensive website “Find a Grave” that Neil posted his photos and text to and that it was digitally searchable. In my ignorance, I never knew that such a resource existed and this for me (as a digital illiterate) was a revealing example of the possibility of finding stuff on line that I would never have guessed existed.

I contacted Neil and he seemed pleased to learn more about this man who, from his point of view, he had hoped to rescue from obscurity. We went on to develop a long-lasting working relationship and he proved to be a master genealogist whose extensive work has provided the main backbone for most of what we know about the Thomas Jackson family genealogy in Reading. Not only did he bring Thomas’s grave stone to light but he did the same for many of his relatives who had also come over from England and had been living in and around Reading. He explored passenger lists of transatlantic liners, voter records, church memberships and residencies. Neil has been a major contributor to the Thomas Jackson story over many years now. I cannot speak highly enough about his willingness to explore any lead that I found may be relevant to the topic. His positive contributions helped keep the impetus of our research moving forward when the most important letters had been transcribed and posted.

It was from Neil that I came to recognize that local newspapers from Thomas’s time might also yield more helpful clues. And again when I explored those sources and overcame some initial dead ends, I found a motherlode of new detailed information about the man, his business and the polemical letters he wrote to the local newspapers. All these newspaper references were extracted, sent to Phil and added to our website to build up an ever more complete picture of the man behind the letters.

What made the process so easy and richly productive of results was that someone had gone to the trouble of making every page of those 150 year old newspapers from this one small town searchable in digital form! (Who would give their time to do such things?) Anyway for the further development of the project it was a godsend. Over half the information that the site currently contains arises from those old newspapers.

Because Thomas Jackson’s business had become massively successful in the light of the need for huge ropes to support the war effort, he was featured in several stories of the “local man becomes very successful” type. There are wonderful long accounts of how Thomas and his brother came to America in 1832 expecting to find work in Philadelphia but in the event, failing to get a job. (See page 5 of newspaper Sept 9 1870) As a result they walked and hopped barges up the canal system until they found themselves in Reading and saw a plot of land they felt would be favorable to build a ropewalk (where ropes were made in those days). The article reports them having a discussion with a Quaker superintendent of the navigation system who warned them they would not be able to make a go of it but nonetheless gave them permission to rent the land for 50 cents a month for as long as they wanted it. That particular article contains a rich and entertaining dialog between the Superintendent and Thomas Jackson (presumably related by TJ to the reporter) that could fit immediately into an entertaining film script of this historical profile. “Thee has pitched upon a rough spot so thee may give it up any time thee pleases for I know thee will do no good here.”

The outcome was that Thomas Jackson, using only his basic wood-working tools, cut down trees, and used the logs to build a shed and started his first American ropewalk. (It turned out that the Superintendent was correct. Their rope walk was twice totally wiped out by floods in the early years.)

The newspaper letters reflected TJ’s constant support for the abolition of slavery and his opposition of the generally accepted politics and values of most in his community. (This stance was a likely stimulus for his later ropewalks twice being lost to arsonists!)

But for me the most poignant and heart-wrenching words ever written about Thomas Jackson appear in one of the reports of his funeral in the local newspaper. (August 12 1878)

“On the coffin rested a cross of flowers and a wreath placed there by prominent colored citizens in acknowledgment of Mr. Jackson’s devotion to the colored race and opposition to slavery”

A rare but appropriate tribute to a white man who pursued his sense of justice by trying to make America live up to the standards that his father had promised him as he sat on his knee as a child back in England.

**********************

This is a very incomplete account of some of the key stages that led to us building the website and learning about the man and his mission.

It omits all sorts of people who gave great help and support. A senior librarian and her colleagues at the University of Florida, a past director of the Historical Society of Berks County who allowed us to use some notes and photographs of the Thomas Jackson ropewalks, and several individuals who for longer or shorter periods were active supporters of the project.

It also reads as a sequential process whereas in practice several things were often moving ahead at once.

As you are aware there is still a whole lot more that could be pursued.

I already have made a special trip to the English town where Thomas Jackson and his father lived hoping to find out more about those early days. However, unlike the old Reading newspapers, the English equivalents are only available as microfiches which take endless searching and delivered absolutely nothing new to me after a whole week of daily library visits. This made me doubly determined that our own websites must feature transcriptions that are totally searchable in order be maximally useful for researchers.

Among the topics I was particularly anxious to explore was whether there were records of Thomas Jackson’s father being the pilloried three times and then locked up for a year for daring to speak out in support of America’s wish to become independent from England! (Another tidbit from a newspaper letter written by Thomas Jackson). There must be a literature somewhere about other Brits who stood up for America’s independence and paid a price. That whole topic sounds interesting.

Another unknown is to whether any of Thomas Jackson’s other letters were ever published. Also whether there is any evidence that his letters actually had any political influence over there. Again efforts to find information in the local (digitally unsearchable) newspapers went nowhere.

Yet again, I suspect Thomas wrote letters to dignitaries and leaders of the abolition movement while he was also active sending his reports back to England. We were thrilled to learn of one such example of a letter to Thaddeus Stevens sent to us from the Library of Congress. I suspect that he would also have contacted leaders Lloyd Garrison and others too. He certainly engaged in a long newspaper dialog with Horace Greeley (April 6th 1871) and seemed always to be looking for a platform for his opinions. Were he alive today, I suspect he would be another vigorous and unrestrained user of Twitter!

WHERE WE GO FROM HERE:

David Machin passed away about 2 years ago so it is now back to me if more is to be done on the Thomas Jackson project. I have always wanted that his story be told at a level that would be interesting to the general public and so have consciously tried to garner marketing materials that might persuade others (it is always “others”, notice) to take over and develop the project.

Your suggestion that there may be value to a parallel donation reflecting how we added background to the letters has set me thinking. The above narcissistic notes are in part intended to get us both to evaluate what, if anything, that would mean. What would you be wanting? Old emails I sent to Phil? Letters from collaborators? A summary of what we now know about the background of Thomas Jackson from the contemporaneous newspaper references? I would be interested in learning how your initial thoughts may now be abandoned or possibly crystalized by the above anecdotage.