Passionate Abolitionist and

Witness to the American Civil War

Passionate Abolitionist and

Witness to the American Civil War

English newspaper article of one of TJ’s letters on witnessing a slave market

A vivid example of Thomas Jackson expressing his hatred for slavery and his successful attempt to get his reporting published in the Ilkeston Pioneer, the English newspaper of the local town where he grew up. (He was doing this, as we know from other letters, in the hope that it might influence British readers to actively support Lincoln and the abolitionist movement and not the Tory Party whom he felt was supporting the South.)

This account of Thomas Jackson’s first encounter with a slave market has proved to be the most popular letter in this collection. Because of this, in the Ambassadors’ Notes we have added some other letters from Britishers who wrote about their own reactions to slave markets while visiting America about the same time.

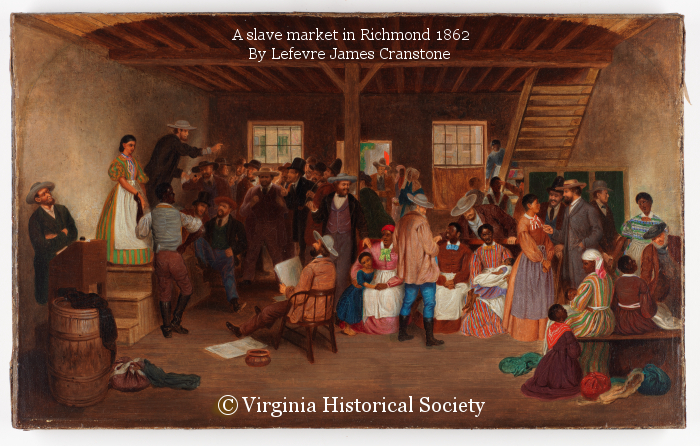

Slave Auction in Richmond by Lefevre Cranstone

Like Thomas Jackson, Cranstone was by origin an Englishman who, on witnessing this American Slave market was moved to describe it in depth in an English newspaper. (Hemel Hempstead Gazette Dec 29 1860). Both these authors forcefully expressed the disgust that the experience caused in them. Cranstone starts “It is in the slave auction rooms where the horrors of the system are most palpable to the eye. No pen can adequately describe scenes so revolting to the mind of the stranger . . . ” With this firm opinion in his mind, he not only described the scene in words but went on to produce this remarkably detailed painting of the people, the emotions and the degrading process of selling people as property. (For more see Lefevre James Cranstone by Donald L. Smith.)

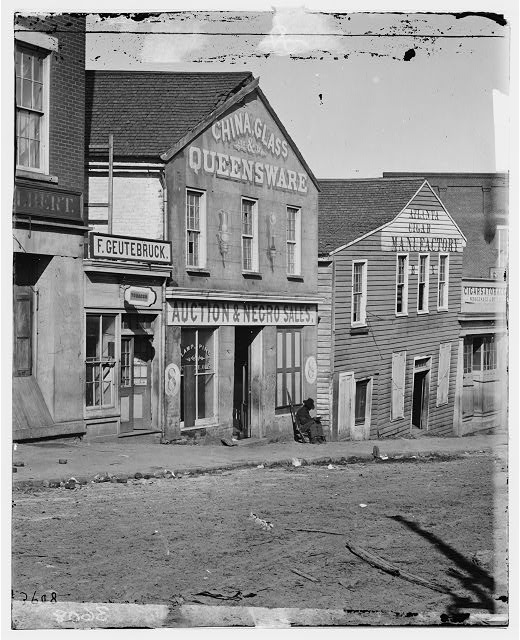

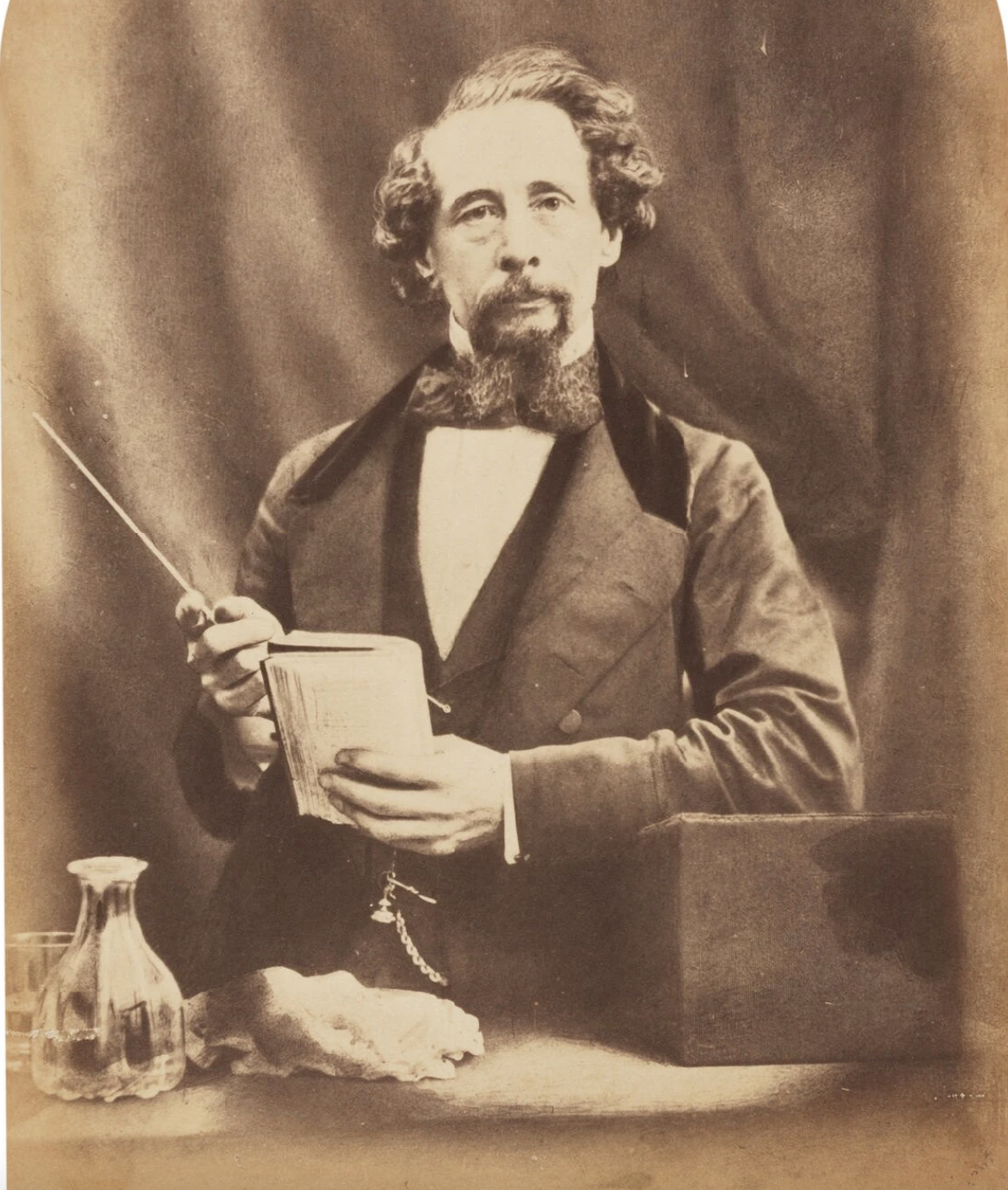

The Slave Market. Atlanta. Georgia

One of a stero pair showing a man with a rifle outside a building announcing “Auction & Negro Slaves.”

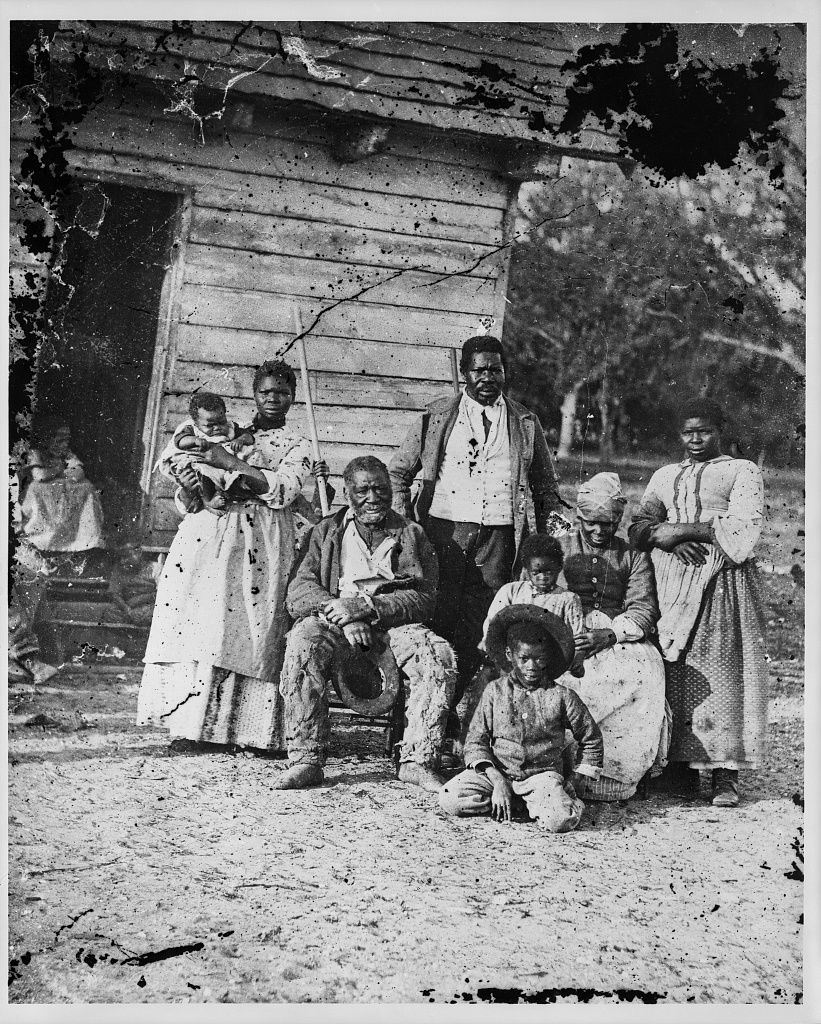

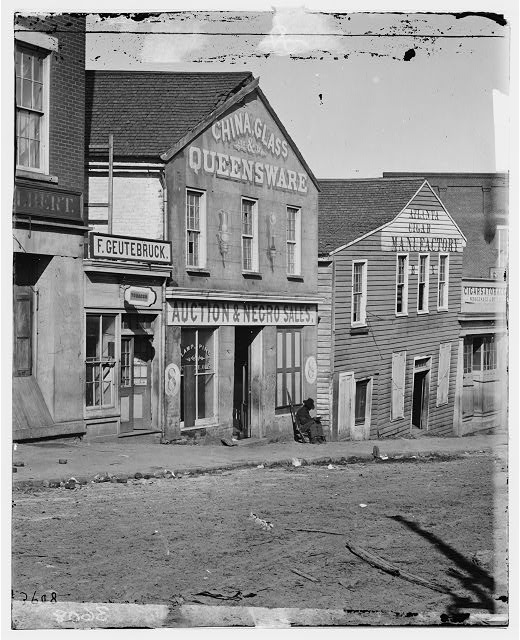

Five generations of slaves in 1860’s living on one plantation.

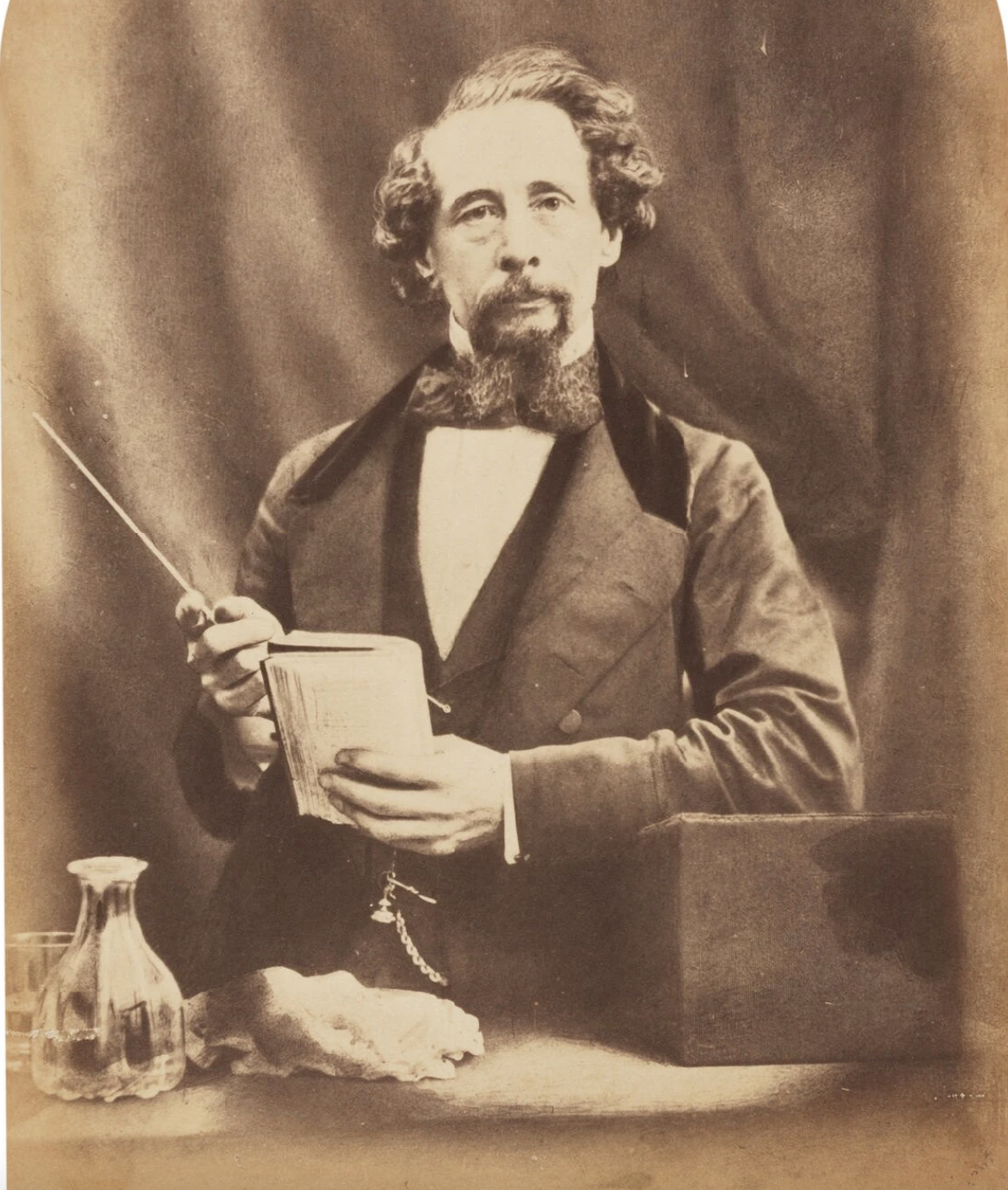

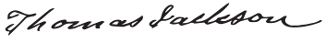

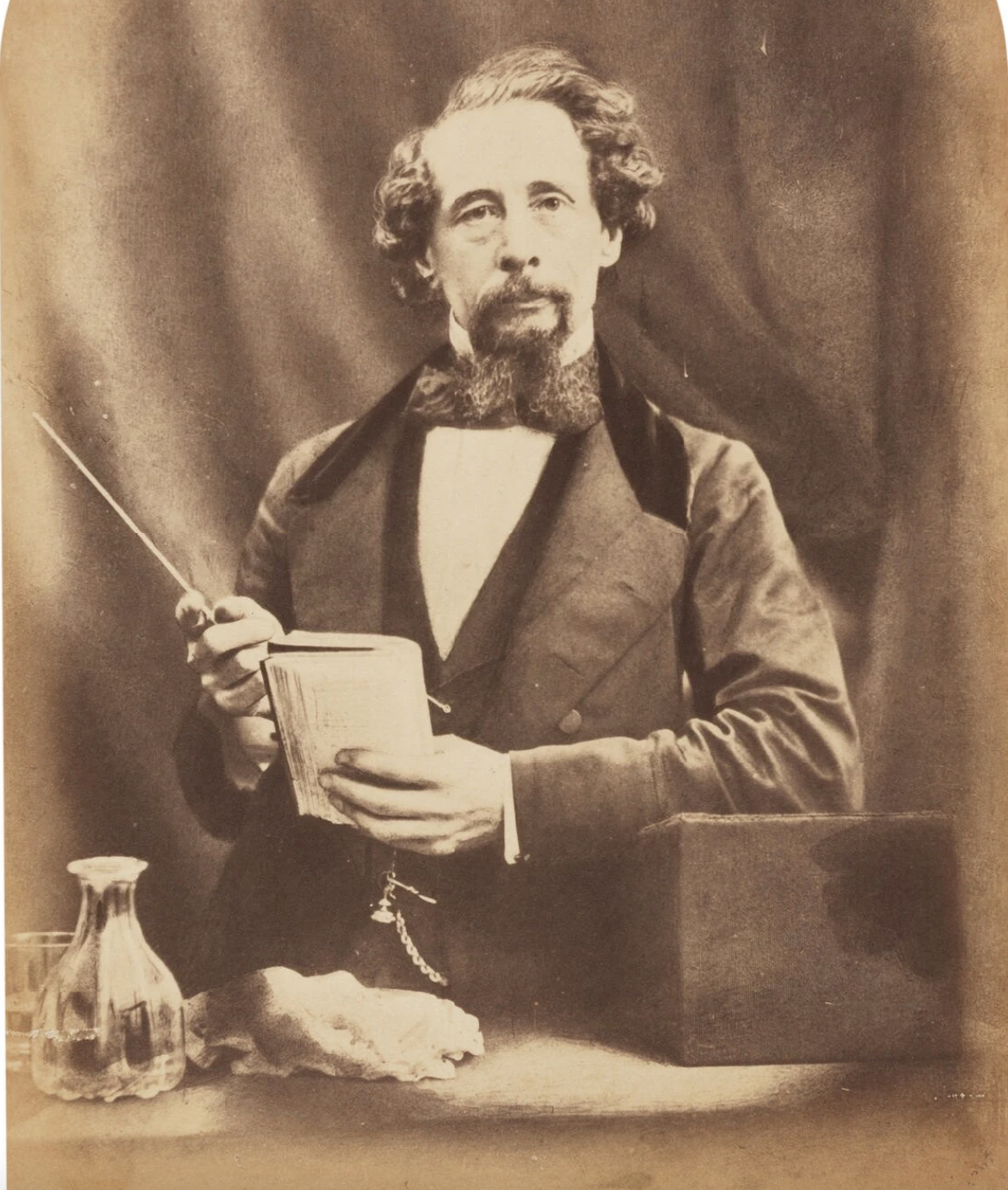

Charles Dickens conducting a reading from his works 1858.

Source: National Portrait Gallery London. Item P301(20)

Sources

1. Image courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society. Oil on fabric, 1863, from sketches made during a visit in 1860

2. © Library of Congress. Reference www.loc.gov/picture/item/2011647092?

3. © Library of Congress. Reference www.loc.gov/picture/item/98504449

4. Image and notes courtesy Missouri History Museum

Letter from Thomas Jackson written August 12, 1862 from Philadelphia and published in the Eastwood, England, area news paper September 11, 1862

A NATIVE OF ILKESTON IN AN AMERICAN SLAVE MARKET

The following letter is from the pen of Mr. Thomas Jackson, who was a resident at the Ropewalk in this town, and who will doubtless be remembered by many of our old townsmen.

“Fifty years ago my father used to take me on his knee and tell me of America — the United States of America. He described it as a far-off land, “flowing with milk and honey, where every man sat under his vine and under his fig tree, and none to make him afraid.” He praised the Government as the only one then free, and based upon the sovereignty of whole people, mildly, justly, and economically administered for the good and protection of all, in the full rights and privileges of the largest liberty that can be properly and justly enjoyed by a civilized nation. He filled my boyish fancy with such glowing ideas of free America, that I determined to go to that highly privileged and prosperous country when I became a man, and, my own master.

More than 33 years ago I emigrated to America, and settled in one of the most prosperous of the free States. I was kindly welcomed and found many good men and kind friends. I had to work hard, but I soon had a good home, acquired property, and was prosperous and happy. I saw nothing of slavery.

My father had never mentioned such a thing as American slavery. I never dreamed that such a thing was possible as liberty and slavery existing together under a free Government, and just laws.

I was too simple to entertain such an idea. Never thought such a thing could be; do not now think it can be; know now it cannot be.

But about 12 years after I came to America I had occasion to visit a large Southern city on business. The day after my arrival there I saw a crowd of men in one of the principal streets. On going to see what brought them together, I found an auction of slaves in full operation.

I suppose I saw 15 or 20 sold, of all shades of colour from black to three-quarters white. Then they brought out a good-looking, well-dressed, modest, and most interesting young woman, about 23 or 24 years old, and, to all appearance to me, as white as my own English wife. She had a little daughter about three years old by her side, and a beautiful babe of about a year old in her arms, both, for all I could see, as white as my own children at home.

The common law of England makes the status of the child to depend upon the status of the father: but about 1740 the legislatures of the American slave colonies reversed that law, and made the status of the child depend upon the status of the mother. Ever since then the offspring of slave mothers have been whitening, until the very small taint of negro blood is not perceivable in many.

So this woman — this white woman — and her little ones were placed on the auction block and put up for public sale to the highest bidder. The auctioneer began —

“Gentlemen, I have a very interesting lot to offer you now. This woman is a good housekeeper, good laundress, a good sewer and quick with her needle, a good and careful nurse, kind to children, good tempered, trustworthy, and a very confidential servant every way capable of taking the whole charge of a gentleman’s household. She has not been used to hard work, but she is young and a very valuable breeder, and she has two fine healthy children. Gentleman, give me a bid. How much for the lot?”

The “Gentlemen” were a queer looking crowd, most of them a hard featured set of dirty mouthed, rum-drunking tobacco chewers, seemingly not half as white as their victims, who gloated over the poor woman and her babes they were bidding for.

And there stood this helpless daughter of slavery — with 1/32nd or 64th part of negro blood in her veins, which, in America increases feminine loveliness by adding largely to its softness and delicacy — there she stood under the rude gazeof these republican “gentlemen” — these slave loving champions of liberty, liable to become the property, and entirely subject to the power and the lust of the grossest brute among them, if he bid high enough!

There stood this most interesting young American mother, with her mild large, dark, tearful eyes and most interesting features, evidently feeling her degradation, the very picture of desolation and despair, pressing her beautiful babe to her bosom almost convulsively, her little daughter clinging to her dress in alarmed wonderment at the strange scene she was for the first time a part of.

There stood this most interesting group — the most melancholy spectacle of democratic barbarism ever witnessed in society claiming to be civilized — there they stood and the bidding and gloating went on!

Great God! Thought I, Is this the land of civilization, freedom, and just laws? Is this my poor father’s far-famed America? Is this “the land of the free and the home of the brave?”

There are times of astonishment when the human mind crowds the thoughts of long periods back into a few passing moments. I looked with appalled amazement on that horrible sight only a few minutes; but in those few minutes I dreamed over again my 30 years dream of American liberty, and found it but a dream! I walked away with a heavy heart, a wiser and a much sadder man than I was before.

That was 20 years ago. I have lived in America ever since; but from that hour all respect for the Government, and the people who uphold it, was gone. I have continued to look upon the pro-slavery party — and they are a great majority North as well as South — with a perfect loathing.

The barkeeper of the hotel I stayed at knew the owner of this poor young woman, and said that owner was the father of her children. He had become tired of her, wished a change, and all the favour he showed her was — to send her and her (and his) two children to auction, to be sold together in one lot, and not separated while he owned them.

When a British aristocrat seduces a girl of lower degree if he does not marry her, he feels in honour bound to provide for her and his children; but the American slaveocrat is not influenced at all by any such fine feelings. The honourable and paternal are never thought of; the pecuniary alone entirely predominates; and American laws and institutions encourage him to send his children and their mother to the slave mart, and put their price in his pocket to minister to continued luxury, laziness, licentiousness, and slavery!

These are the men who, having ruled free America for fourscore years, because they lost an election, have rebelled, and are now in the field with four hundred thousand men to upset the Government; and the European aristocracy and cotton lords are sympathizing with them in an attempt to establish a nation founded entirely upon the infernal and revolting institution of human slavery, with all the accursed concomitants I have just described.

But slavery must perish, with all its abettors. Its Northern toleraters and its Southern defenders are slaying each other by thousands, and the wrong done to that poor mother and her lovely little ones is now being amply avenged.

Richmond, where I saw her, is now one vast hospital of wounded and dying men. Thousands and tens of thousands have fallen in battle near there. The country in all directions is being desolated by fire and sword, shot and shell. Virginia — the mother of five American presidents and millions of American slaves — that has been breeding the poor victims of human villainy, with which to supply the slave markets of her sisters in sin for nearly two hundred years, is now the main battle ground of the vast contending armies of white-faced American aristocracy, and will be laid waste and desolated entirely before the fighting is all over.

Such are the historical retributions of Providence! Such are the dealings of almighty and eternal justice!

Philadelphia, August 12th, 1862

Most readers who encounter Thomas Jackson’s Letters for the first time cannot but be impressed by his unswerving efforts to defeat slavery.

He clearly saw the moral and ethical outrages of the institution and took actions to support change. Respect and admiration for that is well deserved and, as a result, it is easy to expect that Thomas Jackson would have a comparable sensitivity to other issues of the day. However he shows himself to have human imperfections too. For example, it is difficult to read this letter and not feel that somehow Thomas Jackson felt more sympathy for a white slave being ill treated than for a dark skinned one.

An alternative explanation may be that, in writing to influence the while population of his home town in England, he felt that this focus was most likely to gain sympathy for his cause in the hearts of his readers.

This particular Thomas Jackson letter is so powerful and explicit that it stays in the mind of virtually everyone who has encountered it. However, to put it into perspective, we should know that other British people who visited the slave markets of Richmond and elsewhere also expressed their horror and disgust at what they witnessed with equal eloquence.

Their reactions are of course valid but, as Britishers ourselves by birth, we Ambassadors need to acknowledge that Britain was a major party driving and supplying the slave trade for many years. However, the country had come to recognize its immorality and withdrawn from it about 40 years before America did. Thus there were many literate people in England who had grown up in a country where slavery was never experienced and so when they encountered the realities of slave markets in America, it delivered a jarringly unacceptable experience.

Charles Dickens conducting a reading from his works 1858.

Source: National Portrait Gallery London. Item P301(20)

“Conceive this dismal looking (empty slave hall) with no one in it but three negro children, who, as I entered, were playing at auctioneering each other. An intensely black little negro, of four or five years of age, was standing on the bench, or block as it is called, with an equally black girl, about a year younger by his side, whom he was pretending to sell by bids to another black child who was rolling about the floor.My appearance did not interrupt the merriment. The little auctioneer continued his mimic play, and appeared to enjoy the joke of selling the girl who stood demurely by his side.”

(The last two accounts are sourced from the book “The Richmond Slave Trade” by Jack Trammel. 2012- The History Press)

The Slave Market. Atlanta. Georgia

One of a stero pair showing a man with a rifle outside a building announcing “Auction & Negro Slaves.”

Five generations of slaves in 1860’s living on one plantation.

Charles Dickens conducting a reading from his works 1858.

Source: National Portrait Gallery London. Item P301(20)

Sources

1. Image courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society. Oil on fabric, 1863, from sketches made during a visit in 1860

2. © Library of Congress. Reference www.loc.gov/picture/item/2011647092?

3. © Library of Congress. Reference www.loc.gov/picture/item/98504449

4. Image and notes courtesy Missouri History Museum