Passionate Abolitionist and

Witness to the American Civil War

Passionate Abolitionist and

Witness to the American Civil War

The date range of the materials in the Thomas Jackson collection covers an important period in the development of national postal services.

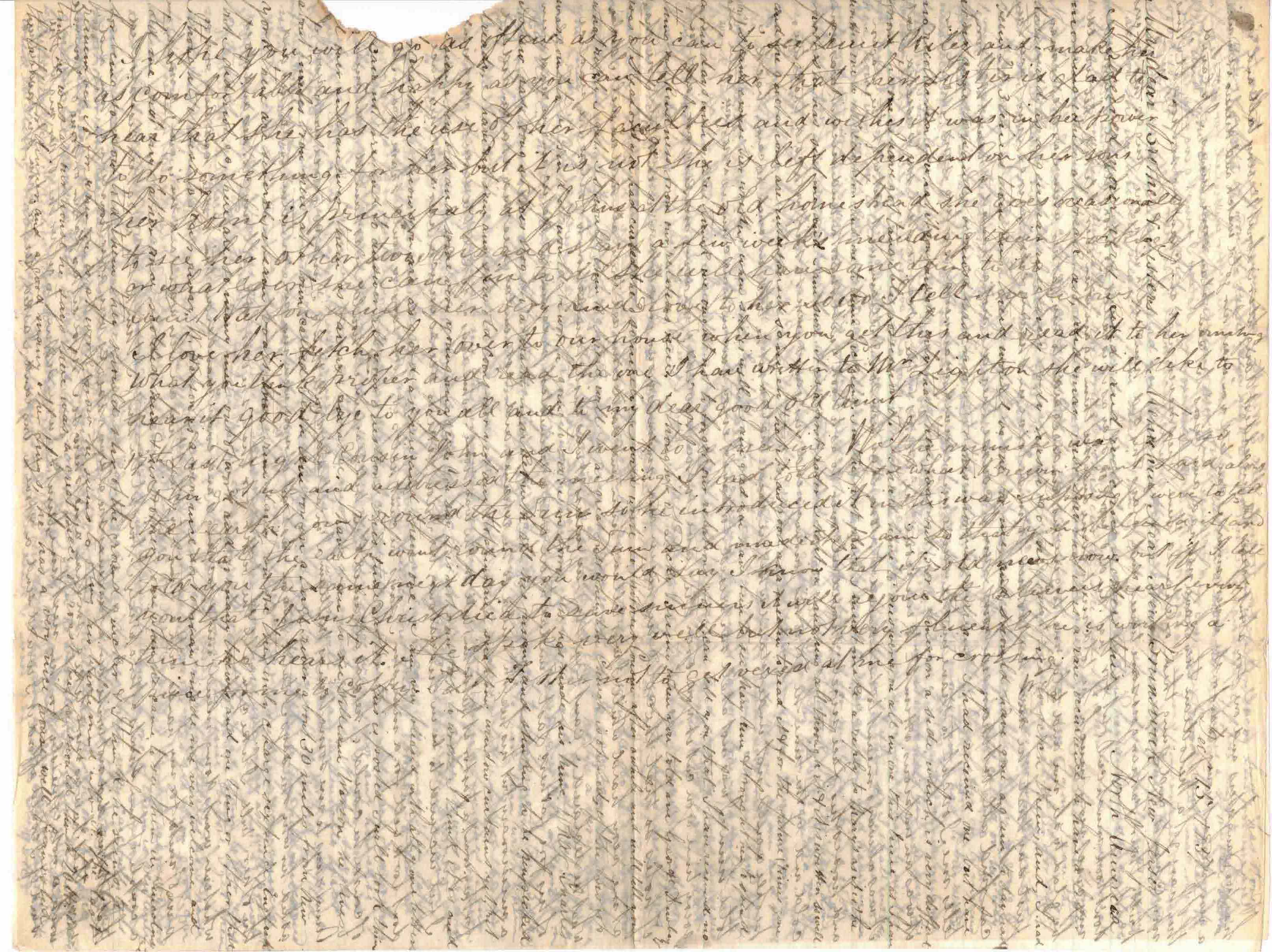

These British postage stamps from the reign of Queen Victoria are all that remain from what now we would view as vandalizing part of this historical collection of well over hundred letters.

To understand how this happened, the Reader needs to appreciate the circumstances in which the collection was first explored. It was during the blackout conditions of the second world war in England and families were more focused on surviving bombings and keeping spirits up rather than exploring what were at that stage just a box full of old and obscure letters that no one had been able to interpret.

The first official postage stamp was produced in 1840 and that was an English “Penny black” with a design similar to these stamps. (The first American postage stamp appeared shortly after in 1847 but sadly we have no examples of those in our collection.)

The Thomas Jackson collection includes many “stampless covers” from prior to 1840. They typically had no envelopes and consisted of a sheet or sheets that were folded, addressed and were closed with a wax seal, sometimes with a personal imprint pressed into the wax.

A Side Issue:

In elegant society individuals would have their own distinctive seal, sometimes a family coat of arms or personal monogram, and this would be fashioned into a finger ring – so that imprint could serve as a signature and hence usually termed a “signet ring” and worn on the little finger of the non dominant hand.

The design would be etched in reverse so that when pressed into wax, it would show in the correct manner. Signet rings or similarly engraved cylindrical seals have been in use since 3500 BC and remained as an authorized signature in many countries for countless generations.

The seals on the letters in the Thomas Jackson collection seem very undistinguished and probably were made with a simple, cheap commercially produced design that appealed to the purchaser.

For more information see the Ambassadors’ Notes within.

These first 3 stamps cover simple postage for letters within England. “POSTAGE ONE PENNY”

The last two stamps had a different function. These were used to make handwritten documents have the force of legal approval. Each would have been attached to a legal document and the money for the stamp would go to the government. Hence POSTAGE AND INLAND REVENUE * ONE PENNY.

Only when the revenue stamp was affixed to a document and it was stamped (or more commonly written over) does the document become legally valid. The final stamp is a good example of that practice.

Ambassadors' Notes are commentaries added by the original founders of the Thomas Jackson letters and are intended to add context to the transcription that proceeds them. Other comments by visitors may have been offered in Recent Research and Commentaries in the seventh panel of the homepage.

The earliest overseas mail arrangements depended on common carriers with little uniformity or coordination. Such enterprises were the main method of carrying and delivering the mail until the establishment of a a royal monopoly in England and postal system in colonial America. Benjamin Franklin who was the deputy postmaster general for the American colonies in 1753 and then the first postmaster general of the United States in 1775. He expanded the service not only in USA but also to and from England.

In both countries the speed and frequency of the mails were improved in large part by extensive road building and improved designs to a series stage coaches running between establishing coaching inns. (In England in 1830s, they were even able to push the speed of stage coaches up to 10 mph!)

Another useful perspective to bear in mind when thinking about the influences impacting mail services was the reality that there were far fewer literate people as a percentage of populations and that relatively few organizations had interests outside their own neighborhoods in those far off days.

Before the days of postage stamps (May 6,1840 in England; July 1 1847 in America) letters had to be taken to a post Office where the post master would note the postage by hand on the top right hand corner. The sender could either pay for the service in advance, allow the recipient to pay on delivery, or pay for part in advance and allow for the remainder to be paid on delivery.

The postage rates were based on the number of sheets, the weight of the letter and distance it had to travel. Pricing this became ever more complicated with overseas mails and the accounting systems required to administer this multi-variable system became the biggest cost of running the mail services in the early days.

However, the high cost of postage had a large impact on many of the letters in our collection. This lead to a series of strategies that the many of the authors (but not Thomas Jackson himself) used to keep the rates down.

The first approach was to use onion thin sheets of flimsy paper to keep the weight down. We have many such letters that would be blown off a table by the slightest breath of wind and which now seem risky to even pick up by one edge.

Additionally and strikingly, it was common to write on one page of the letter in the normal way but then to turn the paper by 90º and reuse the same page by writing across the first side.

This style of cross writing was the norm for many of the correspondents in this collection (eg William Slater when he was in America) but was viewed with stern disapproval by some of the recipients (eg his father). The students who have helped organize and transcribe many of the family letters from this trove started off by being relatively unfamiliar with reading manuscript in two directions now the universality of digital communications is the norm in their lives. However, with effort and dedication, they were finally able to “get their eye in” and do good job of extracting meaning out of these crossed letters.

(Literary historians may be interested to learn that Jane Austen, Henry James and Charles Darwin also wrote “crossed”, sometimes called “cross hatched”, letters similar to those we have have been dealing with here.)

Huge improvements in postal efficiency came from unifying the postage for half-ounce letters wherever they were to be delivered in each country (or major sections of it). The very earliest stamps had no perforations to separate them one from another. Instead they were printed on pregummed, non perforated sheets and the post office clerk used scissors to cut out each stamp.

The Thomas Jackson trove has a wide variety of envelopes and stampless covers that will repay study by those interested in mailing styles from 1800 – 1900 in America and England.