Passionate Abolitionist and

Witness to the American Civil War

Passionate Abolitionist and

Witness to the American Civil War

Wilson Chinn turned out to be a thread that led us to a whole new awareness of other abolitionist efforts that were under way in Thomas Jackson’s Day. This image became one of the most widely copied and circulated photos during the American Civil War because it so boldly illustrated the horrors that could occur under the institution of slavery. Here you see just one slave who had been tortured and degraded by being branded on his forehead with the initials of his former owner, Volsey B. Marmillion. Surely there can be no clearer example of how some owners considered their slaves just as items of property that could be treated like livestock.

Adding to this shocking image of the man’s branded forehead, most of the photo is taken up with various equipments of punishment and torture that were in use at the time. There is the obvious punishment collar (intended to make sleep near impossible) leg irons and chains as well as wooden paddle drilled with small holes. (Why the holes? Well when thrashed hard against the bare skin, the paddle produced large blisters wherever the holes were. And, when these burst, they were intensely painful – or if not, the effect could easily be increased by applying salt!)

In summary, this one photo is overflowing with evidence that the institution of slavery could lead to barbarous inhuman cruelty. And although all the ingredients making up this image are true, this photo has clearly been posed to illicit horror and sympathy and thus can be seen as a powerful propaganda tool for the abolition cause. That no doubt was the reason Thomas Jackson sent it back to his relatives in England.

Most people who encounter this image can never forget it. They react to it impulsively as a barbaric scene of horror. However few viewers give a thought to dig deeper and to question what this man’s back story was prior to this famous photo being taken.

We came to learn that nothing was known about how Wilson Chinn came to be branded until we discovered that “our” Thomas Jackson had actually met him in person and thus had the chance to leave us -and the world- his notes about Wilson Chinn’s circumstances.

So, nearly 200 years after this photograph was taken in a studio in New York city, we learn that

“He was a methodist preacher among his fellow slaves. And because he spoke of their wrongs, his owner branded him on the forehead and made him wear the pronged iron collar and leg shackles, night and day for a whole year & put an iron gag in his mouth when he was not at work.”

In addition to these instruments of torture, Thomas includes a personal assessment about the man.

“He is a very honest, simple hearted good man. More intelligent than laborers usually are.”

And because he recognized that his words may be quoted by others as evidence showing the cruelty of slavery and hence be challenged by those who wished to maintain the institution, he signed off as if he were testifying in the court of public opinion. “This I know be true” Signed Thomas Jackson.”

![]()

We did our best to research whether these or similar personal biographic details about Wilson Chinn had been recorded elsewhere but we were totally unable to locate any comparable details. This and many similarly unique records in the contents of the Thomas Jackson Collection led us to recognize that we were in possession of valuable primary source documents that uniquely covered many incidents of the civil war and the abolition movement. Included with many other revelations were these remarkable personal biographic details about Wilson Chinn.

Initially we had simply transcribed the handwritten notes on the back of this photocard without recognizing its significance or wondering how the meeting had taken place. Finally, struggling for any possible explanation, we wondered if perhaps Wilson Chinn had been taken on a public tour throughout Northern states as a sort of “celebrity attraction”, possibly to raise money for the abolition cause and to help ex-slaves receive an education. We cautiously voiced this “off the wall” possibility to others whose knowledge was wider and deeper than ours. And to our academic delight and astonishment we found that something along those lines did indeed take place and, yes, that is probably how Thomas Jackson had met up with Wilson Chinn in 1864.

We are indebted to Dr Michelle Kroll of the Library of Congress for digging up conclusive evidence that Wilson Chinn and other ex-slaves had been taken on a sort of Lecture Tour at which the public could pay for admission and distinguished white speakers would use the particular circumstances of the ex-slaves to reinforce the case against slavery.

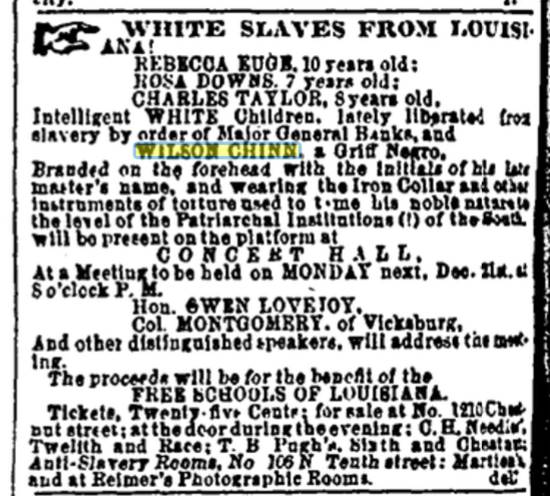

SOURCE. The Press—Philadelphia, Thursday, December 17, 1863.

Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society, Via Readex’s America’s Historical Newspapers Database.

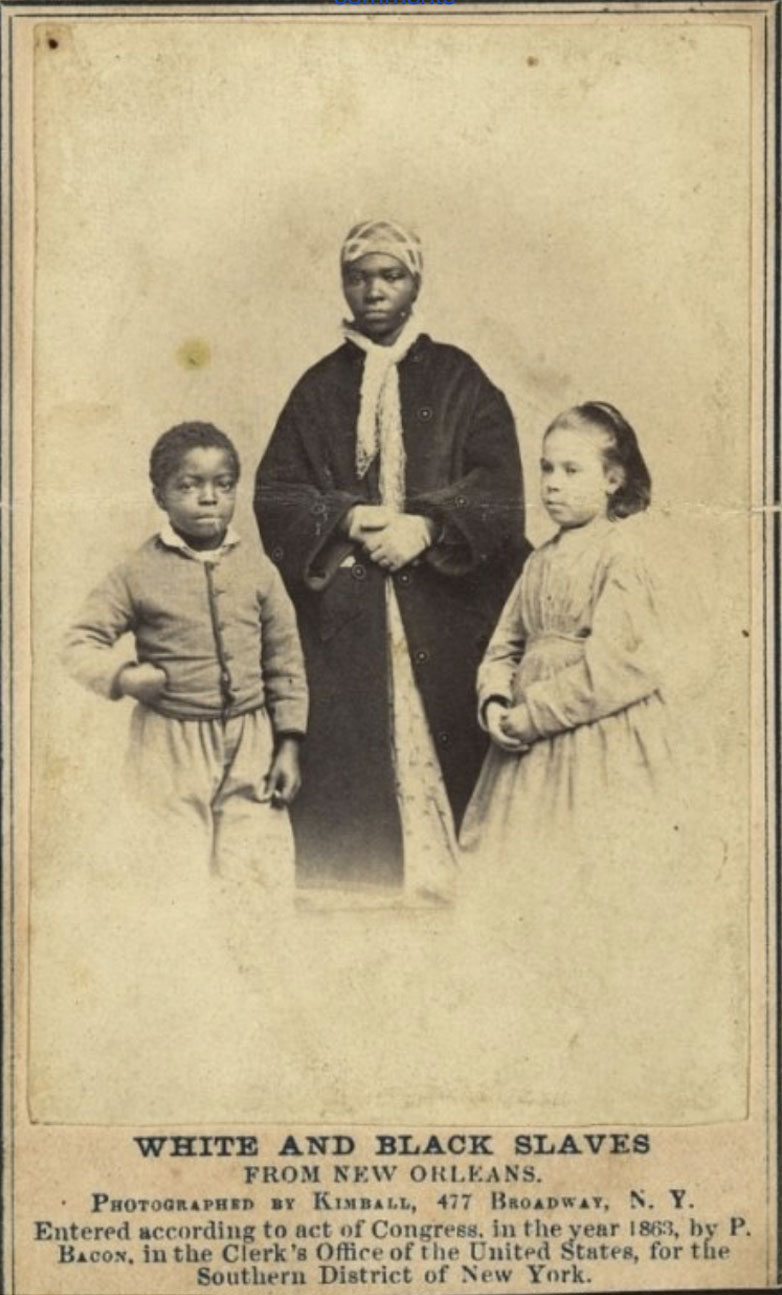

WHITE SLAVES FROM LOUISIANA!

REBECCA KUGE, 10 years old:

ROSA DOWNS, 7 years old:

CHARLES TAYLOR, 8 years old.

Intelligent WHITE children, lately liberated from slavery by order of Major General Banks, and WILSON CHINN, a Griff Negro, Branded on the forehead with the initials of his late master’s name, and wearing thereon collar and other instruments of torture used to tame his noble nature to the level Patriarchal Institutions (!) of the South will be present on the platform at CONCERT HALL

At a MEETING to be held on MONDAY next, Dec.21st at 8 o’clock P.M.

Hon. GWEN LOEJOY,

Col MONTGOMERY of Vicksburg

and other distinguished speakers, will address the meeting.

The proceeds will be for the benefit of the

FREE SCHOOLS OF LOUISIANA.

Tickets., Twenty five Cents: for sale at No 1210 Chestnut street; at the door during the evening: C.H. Needle., Twelve and Race: T.B.Pugh’s Sixth and Chestnut Anti-Slavery Rooms, No 106N Tenth Street: Parties and at Reimer’s Photographic Rooms

Readers will see that the three white, ex-slave children are presented as the main attraction, with Wilson Chinn as only the second item of prominence.

Once again, this seems to play on white northerners being maximally attracted when they realized that folk that looked like them were actually being kept as slaves. Indeed in Thomas Jackson’s famous slave market letter (TJ_letter –1862-08-12) he mainly focuses on describing in detail the anguish of a white skinned slave that was “to all appearances to me, as white as my own English wife. “

So great seemed to be “drawing power” for white folk to see ex-slaves with “white blood” in them that we note that Wilson Chinn is first described as “a Griff Negro” – a term used to describe a black person who supposedly had some white blood in them somewhat similar to a mulatto! The fact that this man actually retained the marks of being branded by his ex-owner was actually listed after the racial description claiming that he too came from white ancestors.

While we were gratified to find that our hunch about TJ meeting with Chinn on a “Road Show” was broadly true, we had overlooked the significance of the other carte de visite picture that was in the same envelope as Wilson Chinn’s picture. The picture of the three named young girls with the title “Emancipated slaves from New Orleans” was mentioned in the same letter as contained the card showing Wilson Chinn.

“I inclose you some photographs of white slaves that have escaped to liberty & come North. I have seen and spoken to them all. The children are from New Orleans. Have been under the care of Northern teachers who went to New Orleans & established schools for the “contrabands” soon after our Union forces took the city. They are very bright beautiful and intelligent children & so white that no one would ever suspect that they had a drop of African blood in their veins. Two of the little girls are exceedingly beautiful & interesting children when spoken with & their innocent hilarity encouraged.”

Now we can understand the reason that TJ “had spoken to them all”. It was because they were in the same touring group that included Wilson Chinn. In other words, these four individuals appeared to have made up one small group of ex-slaves who appeared at the meeting that Thomas Jackson attended.Their purpose was to reinforce an awareness of the pains inflicted under slavery and, in turn, to provide a human dimension to the realities of slavery.

REPORTS FROM ATTENDING PUBLIC MEETINGS WITH THE EX-SLAVES

Newspaper reports of attending such a meeting provide a way to glimpse how the circumstances of the different slaves were wound into the narratives that supported abolition and at the same time debased the character of prominent people in the Confederacy.

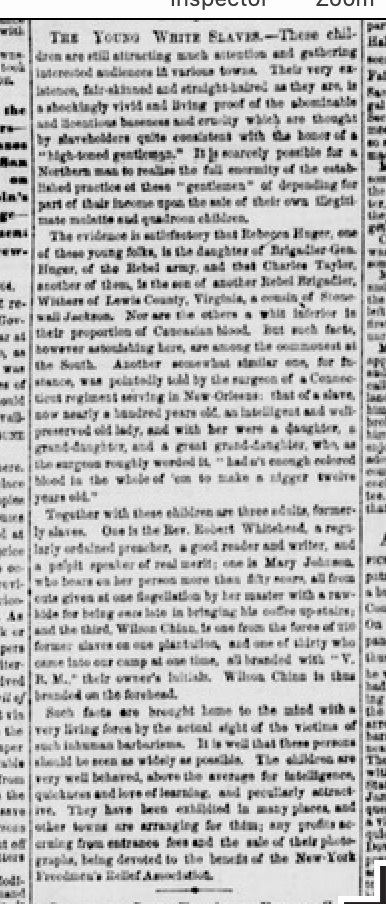

SOURCE: New-York daily tribune. [volume] (New-York [N.Y.]), 01 Feb. 1864. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030213/1864-02-01/ed-1/seq-8/

THE YOUNG WHITE SLAVES

These children are still attracting much attention and gathering interested audiences in various towns. Their very existence, fair-skinned and straight-haired as they are, is a shockingly, vivid, and living proof of the abominable and licentious baseness and cruelty, which are thought by slave owners, quite consistent with the honor of “high toned gentlemen”. It is scarcely possible for a Northern man to realize the full enormity of the established practice of these “gentlemen” of depending for part of their income upon the sale of their own illegitimate mulatto and quadroon children.

The evidence is satisfactory that Rebecca Huger, one of these young folks, is the daughter of Brigadier Gen. Huger of the rebel army and Charles Taylor, another of them is the son of another Rebel, Brigadier Withers of Lewis County, Virginia, a cousin of Stonewall Jackson.

Nor are the others a whit inferior in their proportion of Caucasian blood. But such facts, however astonishing here, are among the commonest at the south.

Another somewhat similar one, for instance, who is pointedly told by the surgeon of a Connecticut Regiment serving in New Orleans that of a slave now nearly 100 years old and intelligent, a well preserved old lady, and with her a daughter, a granddaughter, and a great granddaughter, who as the surgeon roughly worded it, hasn’t enough colored blood in the whole of ‘em to make a nigger 12 years old.”

Together with these children are three adults formally slaves. One is the Rev Robert White, a regularly ordained preacher, a good reader and writer, and a pulpit speaker of great merit. One is Mary Johnson, who bears on her person more than 50 scars all from cuts given at one flagellation by her master with a raw-hide for being once late for bringing his coffee upstairs. On the third, Wilson Chin is one from the force, one of the force of 210 former slaves on one plantation, and one of thirty who came into our camp at one time, all branded with “V.R.M.” their owners initials. Wilson Chin is thus branded on the forehead.

Such facts are brought home to the mind with a very lively force by the actual sights of the victims of such in human barbarisms. It is well that these persons should be seen as widely as possible. The children are very well behaved, above average for intelligence, quickness, and love of learning and peculiarly attractive. They have been exhibited in many places, and now other towns are arranging for them. Any profits accruing from entrance fees, and the sale of the photographs being devoted to the benefit of the New-York Freemen’s Relief Association.

Once we had confirmation of Wilson Chinn being featured as part of such a tour, it led us to many more fascinating facts that opened our eyes to how this particular publicity project came about.

It turns out that Maj Gen. Banks (previously a prominent member of Congress and an ex governor of Massachusetts who was was not a successful leader militarily) being an experienced politician, saw the propaganda value of having photos of some notable emancipated slaves turned into massive numbers of cartes de visits which had become highly popular at that time. So in late 1863 he arranged for eight ex-slaves, including Wilson Chinn, travel to New York under the supervision of Major H Hanks of the African Core, one of the first African American regiments fighting for the Union.

Once there, they had many photos taken of them and it seems that they were probably exhibited in smaller groups to accompany abolitionist speakers in New York and Philadelphia. It is relevant to point out that in TJ’s letter back to England in which he included the cartes de visite of Wilson Chin and the three white girls, he also says that he had “been spending a lot other time in New York and Philadelphia recently”!

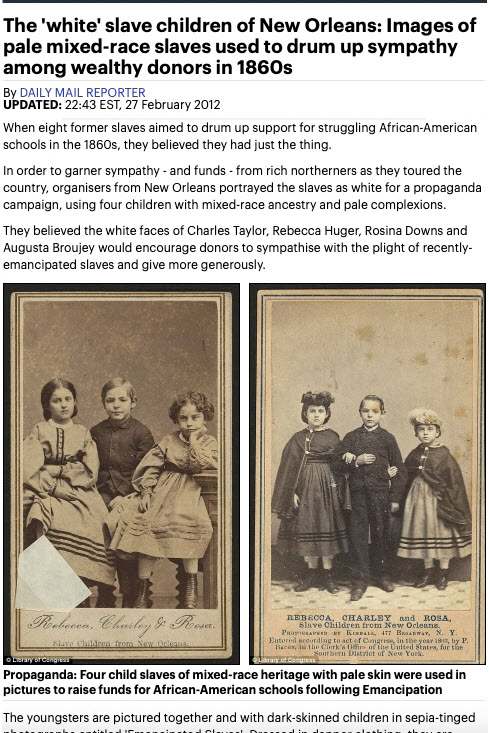

This was indeed the case for once the reality of the “Slaves on tour” was confirmed, it was possible to find further evidence and many different cartes de visites that featured different photographs of three young ex-slaves.

Improbably one of the best assemblages of cartes de visite photographs of groups of these “demonstration slaves” is found in an article in an English newspaper from 2012. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2107458/The-white-slave-children-New-Orleans-Images-pale-mixed-race-slaves-used-drum-sympathy-funds-wealthy-donors-1860s.html

The group that are shown on the card in the Thomas Jackson collection were not identical to those listed in the particular newspaper advert that we now have available. Two of the three young girls in TJ’s photo (Rebecca & Rosa) were also listed as on display in the newspaper advertisement for the lecture event but the third girl was replaced by a young boy, Charley.The three are featured together in several other cartes de visite that are shown in the Daily Mail article and can be seen in the Library of Congress Collections.

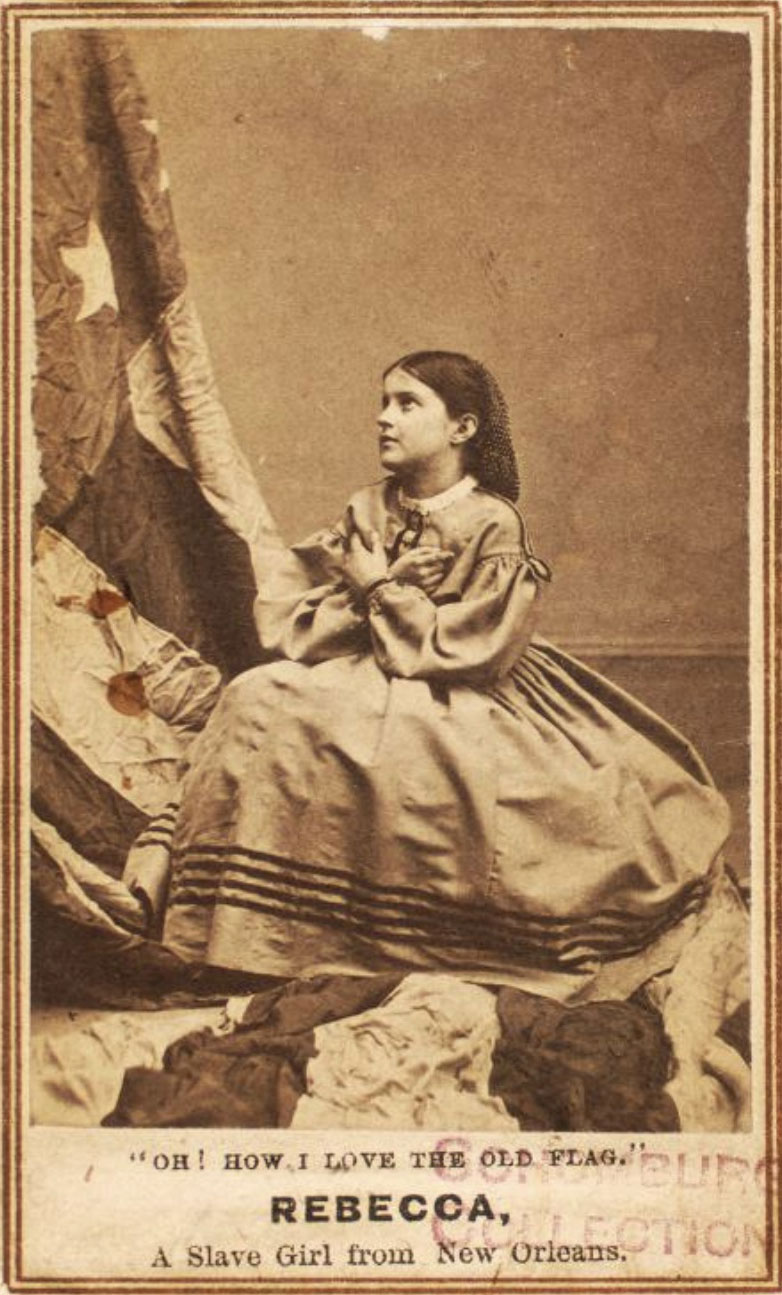

In several of them, the children are shown wrapping themselves in the American flag which must remove any doubt about the main purpose of the photographs.

Source :Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print. from the Gladstone Collection

Source :Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print. from the Liljenquist Collection of Civil War Photographs

These two photos were just part of a series designed to appeal to folks with a patriotic pride about what America represented in particular referencing how it the Federal States represented fundamental freedoms for slaves. These two have been titled to emphasize this fact. “Oh how I love the old flag” and “Our Protection”

Source: Library of Congress Prints & Photographs section, Gladstone collection of African American Photographs

Source :Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print. from the Gladstone Collection of African American photographs.

The carte de visite showing the “white and black slaves from New Orleans” was produced for the same reason as all the other picture cards in this series, namely to sell to raise money for the education of emancipated slaves.

Examining the pictures as a group, It is impossible to ignore the fact that pictures of seemingly “white” ex-slaves were far more numerous and presumably more likely to stimulate generosity in northern audiences than those of black slaves (even though the amount of suffering that black slaves as a group would be every bit as painful as painful as that of “white slaves”.)

The relative lack of demand for photos of black ex-slaves is reflected in the fact that there was one adult black ex-slave in the group for whom we can find no individual photograph. Robert Whitehead was described in Harper’s Weekly as “a preacher who can read and write well, and is a very stirring speaker.” But he does not appear to have featured on any picture card for sale.

In the case of the people in our black and white slave grouping, the 8 year old black boy, Isaac White was praised in Harper’s Weekly as “no less intelligent as any of his white companions” while the black woman was identified as Mary Johnson, “a former cook, who had scars covering her arms and back. They were the result of cuts given to her by her ‘mistress’ and ‘master’ after she was half an hour behind time in bringing his five o’clock cup of coffee”. Presumably similar background information would have been explained as these individuals were introduced to audiences on their tours. This information would be intended to enhance the compassion and sympathy for these black ex-slaves, possibly leading to increased desire to buy a souvenir picture to take home.

Finally, we show the “three children who were turned out of a hotel in Philadelphia on account of color.”

Here we have just 3 of the children that were part of the full contingent of 8 ex-slaves who were exhibited at different public meetings in the north. Judging from the experience of the event that Thomas Jackson attended, it appeared that only a smaller group were exhibited at any particular setting. Our speculation is that most commonly 3 children accompanied one of the adults, all of whom were black.The social conditions in 1860s (and much later) where such that blacks were not welcomed into most public hotels so we suspect that the adult ex-slaves with conspicuously black skin would have been booked into accommodations that were known to welcome them. However it seems likely that the “white ex-slaves” (probably accompanied by the white organizer of the tour -General George H. Hanks ) were booked into a hotel that regularly accepted white guests. However it may have been that when the management recognized that they were in fact ex-slaves (and therefore “black” by the perverse rules of the day.) then they were ejected.

This is just one example of the arbitrary nature of the definition of race which had emerged in the country. The status of the mother determined the status of all her children even if the father was a white slave owner, as Thomas Jackson angrily points out. (1862-08-12).

The lecturers who spoke at the meeting advertised in the Philadelphia Press for December 17 1863 were listed as “Hon. Owen Lovejoy and Col.Montgomery of Vicksburg”.

Owen Lovejoy was a worthy representative of the abolition cause. Wikipedia defines him as “ an American lawyer, Congregational minister, abolitionist, and Republican congressman from Illinois. He was also a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad.” With that background of passion for the cause and great experience as a speaker, he could be assumed to enhance the experience of northern audiences witnessing the ex-slaves from Louisiana face to face.

“Col Milton Montgomery of Vicksburg” is mentioned as a union leader there in 1863 but we know little about him in that capacity but learn than he lost an arm in the battle of Atlanta one year later. Despite that injury, he continued to serve in union campaigns and was honored by President Jackson for his services when he retired.

The important lesson for students of Thomas Jackson is to recall that there were many other active projects in America supporting abolition throughout the civil war. It was his support for meetings seeking funding for the education of ex-slaves which led to him documenting unique insights into the background of Wilson Chinn.

Seen in retrospect, the carte de visite of Wilson Chinn in the Thomas Jackson collection serves as just a thread to illustrate some of the realities of slavery to people in the north and indeed overseas. Thus even though the people in this series of cartes de visite were indeed real, they were photographed and displayed as a vehicle to impact the emotions of viewers in an effort to strengthen the commitment to the abolition cause. in other words its objective was to influence and even twist opinions.

These days the power of emotional messaging is well recognized and now all the elements of the ex-slaves on tour project would be considered propaganda.

As such, this collection is not that different from reports and illustrations that are produced and published today to try to influence the public’s mood about politically divisive issues. It is just one example where the past can be seen being repeated in the present.

As many observers have remarked “ Truth is the first casualty of war.”